Rethinking Investment Risk

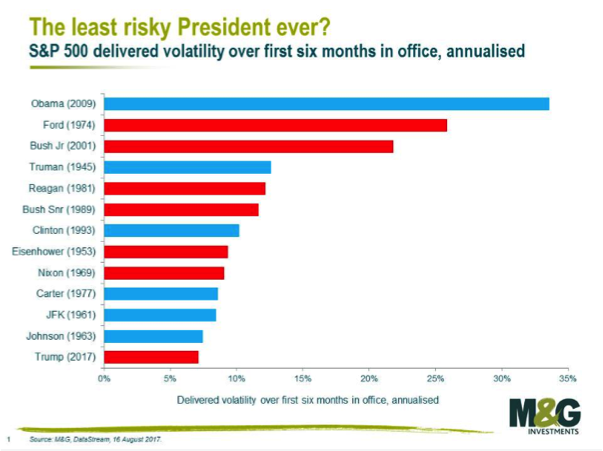

How many people would consider Donald Trump the least risky president of all time? Do you? That’s the sentiment the ill-conceived chart below conveys. Aside from the obvious malpractice of assigning stock market results entirely to the President, there is a subtler and more widely overlooked error lurking—the conflation of volatility and risk.

This is not new. Financial literature has used the two terms interchangeably since at least the dawn of modern portfolio theory in the 1950s. So why do the two continue to be used as synonyms? And how do we define risk if not volatility?

What’s the deal with volatility?

Volatility is simply a statistical measure for the degree of movement around the average. Practically speaking, it matters to your portfolio in two circumstances—when your time horizon is limited, and in emotional reactions to downturns.

By limited time horizon, I am referring to any circumstance that would force you, the investor, to liquidate all or a portion of your holdings over a period of less than 30 years. This could be a required minimum distribution for a retiree, the purchase of a home with proceeds from a sale of securities, or simply withdrawals for ordinary living expenses. These forced liquidations don’t allow you to control the timing of a sale. If an asset is highly volatile, the spread between the highs and the lows is greater, and the possibility that you will be forced to sell at a lower low presents a real risk.

The other reason volatility matters is that investors can become emotional in response to price shocks. If a stock tends to incur large price declines, emotional investors may not be able to stomach the short-term losses, and are again at risk of selling at a bottom. If, however, the investor can overcome their emotional response (and there is an entire body of Nobel prize-winning work describing the difficulties in that), the risk can be reframed as opportunity.

Having strong conviction in the fundamentals of a volatile security potentially provides you with an opportunity to buy or sell at prices not reflective of intrinsic value. So, is it riskier for a stock to move around a lot, or does it simply provide greater opportunity for astute investors?

The misgivings of volatility

Volatility has practical, as opposed to theoretical, imperfections as well; we often use historical volatility to outline the forward-looking risk of an investment. The problem with that, of course, is that it is not necessarily instructive as to future volatility. Knowing what the risks were yesterday is a lot less useful than knowing what the risks are ahead, and I don’t believe historical volatility can provide an accurate measure of that.

Following that logic, if a stock undergoes no significant fundamental change, but spikes in price significantly, it is considered riskier the day after the spike than the day before. The implication, therefore, is that sentiment (which generally moves stock prices in the short term) creates risk, and fundamentals are only a tangential factor. I take issue with that—it just doesn’t provide a complete picture of risk.

To see why, it’s instructive to look at the reverse statement: volatility is an indicator of risk, but business fundamentals create the risks themselves. Think about investing in stocks vs. bonds. A stock is lower in the capital structure, meaning that if a company goes bankrupt, bondholders get paid out in full before stockholders get a penny. It makes sense then, that the stock will be more volatile—after all, there’s a higher likelihood of losing all your money, and any fundamental change in the business is magnified to the stockholder. But in this case, the higher volatility is the indication of risk, not the risk itself.

A better definition of risk—the probability of permanent capital impairment

While we view volatility as a valid component of risk, it does not provide a complete picture. At Bridgewater Wealth, we define risk as the “probability of permanent capital impairment”, or the chance of losing money. Sound simple? Let me explain.

The most fundamental aspect of investment risk is that investors demand additional potential return to compensate for that risk. Would you invest in equities if the expected return were the same as U.S. Treasury Bills? In that light, I find our definition intuitive. Most people I know would demand additional potential return for an investment with a higher probability of losing money, not solely one that moves around a lot.

The three components of our definition of risk deserve further individual explanation:

- “Probability” denotes the uncertainty of future returns. We obviously cannot know future returns ahead of time, but what gets priced in to a security are the estimates we create (however imprecise they may be), either consciously or subconsciously.

- “Permanent” highlights the fact that the losses people care about are lasting in nature. Importantly, losses must occur over a time horizon. Someone that bought into the US stock market in the mid-2000s and sold out in 2008 experienced losses. However, if that same person sold in 2017, they would have earned a sizable return. The investor can only incur a loss over a specific time period, and I submit that people are unafraid of unrealized losses over a time period shorter than their investment horizon.The only reason short-term price declines are scary to investors is in relation to the uncertainty described earlier. Imagine if a stock declined in price, but you had absolute certainty it would recover the losses. Would you still panic in the short term? Future returns are uncertain, so a sudden drop in value can’t be known to be temporary in the moment. By describing risk as a permanent loss, we are better able to match investors’ true risk appetite to their time horizon.

- “Capital Impairment” covers the notion that investors do not demand additional expected return for securities that could spike up in price. This is perhaps the most obvious facet of risk. It’s been empirically proven that investors are fundamentally worried about what could go wrong, not what could go right. It’s why the media tends to frame sharp declines in asset values as ‘risk’ while symmetrical spikes upward are called ‘profits’. Since all investors (including you!) collectively make up the market, the risk that gets priced in must be for fear of the downside.

I believe absolutely that describing risk in this fashion is the most intellectually honest approach. But it can be scary. All of modern finance is predicated on the belief that risk = volatility, and it’s unsettling when you begin to peel back the many layers of financial theory that break down in the absence of that equivalence. Models no longer have the necessary inputs to spit out the perfect solution. Almost paradoxically, the lack of advanced mathematics makes things more complex. Still, directing our focus to the probability of loss should better inform our decision-making over time. I think not doing so would be the biggest risk of all.