Regional Banks: Battered, But Not Beaten

There were many winners in March, with the S&P 500 Index up more than 3.5% and the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index up 2.5%; however, banks were not among them. After the voluntary closure of Silvergate Bank, which focused on banking the crypto industry, depositors began to worry about other banks that might be at risk. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was quickly pushed to the top of the list when it announced a capital raise. Rather than calming nerves, the action created a rapid run on deposits, leading regulators to shut down the bank the morning of Friday, March 10th. By Sunday, March 12th, Signature Bank of New York fell too. Depositors and investors spent the next few weeks trying to identify where cash might be safe and which financial institutions might be next.

How Did The Collapse Happen?

The crisis came slowly and then all at once. The problem for banks, including SVB, is that many of them suffer from an asset-liability mismatch. Their assets, such as bonds and loans, often extend for years or even decades. However, depositors can call back their savings, which are the bank’s liabilities, at any time.

SVB’s business focus made it particularly vulnerable. As the name implies, SVB was the preeminent banker to the startup and venture capital community. They offered a more flexible approach than white-shoe institutions by tailoring relationships to the needs of emerging companies. In exchange for providing lines of credit to these startups, SVB required that companies hold all of their deposits with them, even those well above the FDIC limits.

SVB’s assets grew significantly in 2020 and 2021 as startups raised record amounts of capital and placed them in deposit at the bank. SVB largely purchased bonds with the deposits. Unlike banks in the 2008 financial crisis, SVB did not have risky subprime mortgages or high-yield bonds on their balance sheet. Instead they were exposed to a different risk by extending their duration across high-quality, government-backed bonds.

With no plans to sell the bonds before they matured, SVB marked them on their balance sheet as “Held to Maturity,” which insulated their income statements from price fluctuations. As the Fed raised rates in 2022, yields on comparable instruments went up, causing the value of their bond portfolio to drop. SVB reasoned that they would be fine as long as they didn’t need to sell; it worked until it didn’t.

The cash that startups deposited into SVB in 2020 and 2021 was to fund business plans and payrolls for companies that often have little or no positive cash flow or earnings. As the funding market dried up in 2022, these startups began slowly burning through their cash. Eventually, SVB realized that they might need to sell some of those “held to maturity” bonds at depressed prices. Following their announcement that they were raising capital and preparing to sell some bonds, concerns over SVB’s solvency tore through the startup and venture community. They rushed to withdrawal their funds which, in turn, forced more bond sales and more need for capital. It quickly spiraled out of control leading to an uncharacteristic mid-day Friday shutdown of the bank by regulators.

What’s the Future For Banks?

We believe it is important to separately evaluate the two key risks currently affecting the banking industry: run-on-the-bank risk and earnings risk. Unfortunately, the former is both more imminent and unpredictable.

Bank runs, by their nature, are psychological, with depositors frequently pushing the bank’s financial soundness to the back burner. Almost all banks have held-to-maturity portfolios, which, if liquidated today, would reduce the institution’s balance sheet. Few are subject to the same solvency risk as SVB, but a rapid demand on deposits could impair their ability to continue to function normally. Investors can look for clues, such as the percentage of deposits above the FDIC limits or fair value marks on held-to-maturity securities portfolios or the makeup of their loan book. These factors might expose the likelihood and magnitude of an impairment, but what drives the run is sentiment.

Longer-term, we believe the risk to earnings is more meaningful. In our view, investors are right to question the future earnings power of the regional banking sector.

- Many banks may need to become more competitive with their savings rates, reducing net interest margins (the spread between what they earn on loans or investments versus what they pay to depositors.) The recent crisis provides depositors a reason to review their banking relationships. Many are likely finding that the interest rates on their savings accounts remain very low despite rising rates elsewhere.

- Additional regulatory scrutiny may be costly. After the second largest bank collapse in U.S. history, Congress and regulators endeavor to prevent this from happening again. While many will debate the efficacy of whatever new rules come out of the process, compliance costs are almost certain to rise.

- While investors have focused to date on securities portfolios, community banks have large commercial real estate loans, which could come under pressure as real estate owners look to roll over their debt in the coming years.

- A pullback in lending over the short/intermediate term reduces potential earnings. If, as most analysts expect, banks tighten their lending standards in response to a riskier macro environment and to right size their balance sheets relative to now smaller deposit bases, they will leave profits on the table.

We believe that most of the near-term bank solvency risk is dissipating, but we caution that investors shouldn’t rush into the sector to bottom-fish quite yet. While we think the selling pressure is likely overdone, the crisis’ long-term implications are still forming.

What’s the broader impact?

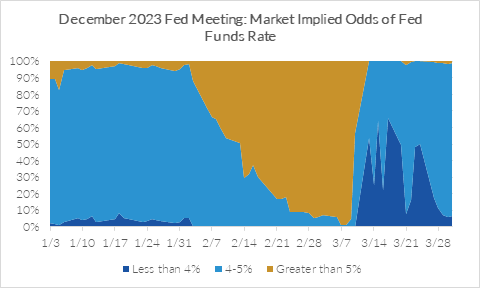

The cracks in the banking system that SVB laid bare have broader implications for monetary policy. There are two main conduits for the flow of liquidity into the economy: the Fed and banks. For the last 15 months, the Fed has been closing the spigot, but bank lending has remained relatively free-flowing. The recent crisis may force banks to moderate their lending practices allowing the Fed to consider pausing. Indeed, after the hot inflation report in January, markets were increasingly expecting that the Fed would raise its benchmark rate above 5% by the end of the year. In response to the turmoil, investors quickly shifted their expectations to a much more moderate (if not looser) Fed policy.

Source: CME FedWatch Tool

For the last several months, we’ve suggested that the turmoil that hit Wall Street in the first half of 2022 was likely a preview of decelerating economic growth for Main Street. While the banking crisis represents the first sign of stress, it may not be the last, in our opinion. After all, the Fed is explicitly trying to take an overheated economy off the boil. A cooling economy typically leads to higher unemployment and slower spending. In many respects, a recession might be seen as a relief to investors that are eager to begin looking forward to the recovery.