Economic Stimulus Boosting Personal Savings Not Spending

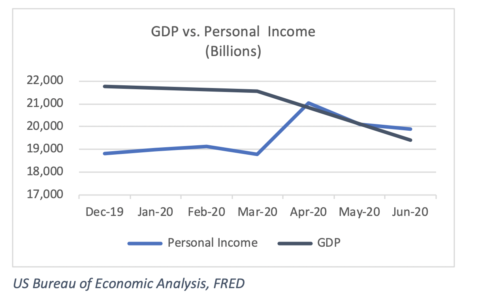

It may surprise you that the deepest recession in modern history has not hit Main Street, yet. While this data glosses over the pain being felt by some households, total personal income is up nearly 6% since the end of 2019. That rise is despite a 32.9% annualized decline in GDP for the second quarter and an unemployment rate of more than 11%. Just as public health officials have worked to flatten the curve of the virus’ impact on health systems, fiscal policymakers have, thus far, muted its impact on household finances. Increased government transfer payments have more than made up for the loss in wages and salary, in the aggregate. Indeed, for the first time since at least World War II, household income is above GDP. The situation is both currently necessary and unsustainable.

Congress is working on the next in its series of stimulus packages. We remain confident that they will reach a deal, but watching the sausage get made is rarely fun. As of this writing, Republicans and Democrats appear deadlocked. To date, Congress has tried to address the economic impact on households in three primary ways:

- Encourage employers to retain their workers through loan and grant schemes like the Paycheck Protection Program. The rationale behind the program is relatively simple. By keeping employees on the payroll now, it reduces the likelihood they are unemployed later. Both Republicans and Democrats seem ready and willing to extend the program for businesses that have had significant revenue declines.

- Infuse cash into households through direct payments of up to $1,200 per person. Both sides of the aisle are in agreement to issue a second round of checks.

- Provide enhanced benefits to the unemployed, which aim to neutralize the financial impact of layoffs. The program (which has now expired) was structured so that by adding $600/week to a state’s standard unemployment benefit, the average worker would have 100% salary replacement. Targeting the average salary has proved controversial. According to a University of Chicago study, because those most likely to be unemployed have incomes below the median, it has meant that 68% of those receiving benefits are making more than they did while working. While Democrats seek to extend the benefits as is, Republicans are trying to target 70% replacement by lowering the benefit to $200/week.

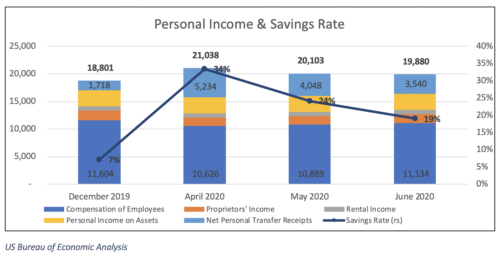

So far, these programs have worked as advertised. Despite the significant decrease in GDP, employee compensation has declined by less than 4% since the end of 2019. Additionally, the increase in transfer payments has more than made up for the aggregate loss.

This spending is not making its way into the economy, however. In April and May, when the majority of the $1,200 checks were issued, households saved 34% and 24% of their total income, respectively. The savings rate now stands at 19% – more than 2.5x the pre-pandemic level. Arguably, there have been fewer places to spend over the last several months with dining, traveling, and shopping in stores largely discouraged. However, if the policy goal of the transfer payments is to smooth rather than defer the impact of the recession on households, we will need to see consumer spending pick up.

While lawmakers could use the tax code to encourage more household spending (i.e. deductions for dining, entertainment, or travel), the current issue is one of consumer confidence rather than disposable income. We hope that policymakers use their platforms to put sensible public health measures in place to give consumers the confidence to leave their homes again.